Worlds Council has endorsed in principle the expansion of the break beyond 32

teams at the WUDC. We propose to first set out the strongest arguments for

each of the three main proposals for how to expand the break and then critically

analyze their strengths and weaknesses. Briefly, those proposals are: breaking

64 teams, breaking 48 teams and a system whereby all teams on 18 or more

break. This essay makes no serious attempt to respond to arguments against any

expansion of the break beyond 32 teams. Such a discussion is surely worthwhile,

but much has already been said about this, a thorough treatment would need to

be more extensive than we have space for, and it is simply not our focus here.

In addressing the specific merits of each of the proposals for expanding the break,

there is a central question that needs to be considered: what is the purpose of the

break and elimination rounds at Worlds? That is, what is it that makes them

different from, say, round 9, and so sought-after by competitors? Understanding

the reasons why elimination rounds are valuable to the WUDC format is a

necessary prerequisite to any discussion of how to change it.

Historical Context

In its early years Worlds was held in differing formats depending on the customs

of the host university. By the late 1980s, with the field of teams typically hovering

around 100-150, the break had settled at 32.1 So, the current Worlds break was

actually designed for a remarkably different state of affairs to the present, with

some 20-25% of the field progressing to elimination rounds.

Some current debaters might understandably assume that the current situation is

the natural way of things, but proponents of break expansion (even to 64 teams)

are not advocating a radical shift in the nature of Worlds so much as a return to the

status quo ante in which elimination rounds were open to a much larger proportion

of the field than now. Furthermore, such a change would bring Worlds more into

line with other tournaments. No one hosting a BP competition with 40 teams

would dream of breaking directly to a grand final, yet this is (proportionately)

what Worlds has done in recent years.

The authors of this paper wholeheartedly agree that the Worlds break should be

a significant accomplishment and should never be ‘easy’ to get into, but this is

not at odds with break expansion, as we shall see below. Once again, the history

of the tournament suggests that concerns about low standards are overstated.

The early World Championships were very different affairs from today’s major

multinational events, attended almost exclusively by teams from six Anglophone

nations for whom the trip to Princeton, Sydney or Glasgow might be one of

only three or four competitions that they attended during the year, in contrast to

today’s well-developed national and international debating circuits.2 While the

field at a contemporary WUDC tournament obviously includes a great many

teams who do not realistically have a shot at making the main break, there is little

doubt that as the competition has grown, so too has the number of well-drilled,

competitive teams who would not be out of place in an octofinal; as has the

difficulty of making it that far.

The Purpose of Elimination Rounds

What, then, is the function of elimination rounds at Worlds? The simple answer

seems to be that they are a device for sorting teams by quality. Of course, at the

end of preliminary rounds, we already have such a list (“the tab”), which we use

to decide who breaks. So, if the sole purpose of these rounds were sorting, then we

would need evidence that a single elimination format does a better job at sorting

than four or five more power-paired preliminary rounds.

We are not confident that elimination rounds do a better job at sorting teams for

three reasons. First, they start by largely throwing out a lot of relevant evidence

from the rounds that have already occurred. Second, if we assume that the

seeding for the single elimination bracket (i.e., the tab ordering) is not particularly

accurate—which we must assume, or else there is no good reason for additional

sorting—then the single elimination format does not even theoretically do a good

job of sorting anyone beyond the best two teams.3 Third, single elimination is a

poor sorting device for even the best team (especially four rounds of it) because

even excellent judging is imprecise and even excellent teams can get put in very

tough situations (e.g., by another team’s bizarre argumentation).

If you think that none of this is a persuasive reason for abandoning single

elimination rounds, we agree. However, it does show that there are important

functions of the elimination rounds beyond sorting.

These other functions include: A) creating an exciting, high-stakes set of

increasingly high quality debates; B) providing a learning opportunity for

viewers; C) generating a celebratory culmination of the tournament; D) giving

an award in its own right for debaters who have performed well; and, E) providing

an opportunity to evaluate debaters’ performance in front of an audience. All of

these are good reasons to keep single elimination rounds, and indeed to expand

them.

Elimination rounds are very good at fulfilling function A. They bring an element

of uncertainty to the competition, like a sporting event in which top teams may

be humbled by underdogs before the final. Some contend that it is somehow

unfair for a skilled team to run the risk of being eliminated by a “wrong” decision.

Indeed, there are those who would even be happy to see the world champions

of debate selected on the basis of the team that topped the tab after 12 or 15

preliminary rounds of debate. But where would be the excitement in that?

Elimination rounds also provide what for many competitors will be a rare

opportunity to watch, listen to and learn from the best of their contemporaries

(B), and the value of function C is fairly self-explanatory. All three proposals

to expand the break will accomplish functions A, B and C to roughly the same

degree. The difference between the proposals primarily lies in five things: 1) the

practicality of their implementation; 2) the fairness of their implementation; 3)

how effective they are at sorting teams, such that the higher quality team are likely

to progress further in the tournament; 4) how well they perform function E,

evaluating debaters with an audience; and, 5) how well they accomplish function

D, distributing a valued award.

Let us briefly consider the function of the break as an award. There are very few

trophies given out at Worlds, but being able to say that one “broke at Worlds” is

in itself a significant intangible award. The two important most aspects of this

award’s value are its exclusivity and its fairness. Although giving and getting

awards (even intangible ones) is nice, as the percentage of debaters who break

increases, the prestige of this award decreases. This is surely one reason we can

all agree that breaking 128 out of 350 teams would be a mistake, even if it were

practical. But at the same time, breaking only 8 teams would be a mistake because

such a distribution is too stingy, even if it were a more reliable sorting method.

The point here is that there is some admittedly vague point that is the ideal

compromise between being too stingy and excessively devaluing the award of

breaking. The most objective means of estimating the prestige of breaking across

years is to calculate the percentage of participating teams that break. So, let us

look quickly at how these three proposals would have affected these percentages

over the last 10 years and with a couple hypothetical larger fields.

Basically, the lower the percentage of the break, the higher the prestige of the

award, but the fewer the people who get to enjoy it. The top two lines are

included to frame the perspective on what some see as the likely future growth

of the tournament. Obviously some of the older data is of limited usefulness,

since future tournaments are unlikely to have fewer than 200 teams, but they

do provide an important historical perspective. As noted above, in the 1990s

there were 32 teams in the break, with only about 150 teams in the field, making

the portion of teams breaking over 20%. But, history provides no authoritative

guidance on the correct percentage of breaking teams.

Proposal 1: Breaking 64 Teams

If the decision to expand the WUDC break is to be implemented, there are

several reasons to think that a 64-team break is the most sensible and elegant

solution. First, and most obviously, it is the simplest method. Doubling the size

of the break adds an extra round, but leaves the structure of a Worlds tournament

otherwise unchanged. Logistically there is no significant problem adding an extra

elimination round into a WUDC schedule. Once the organisational obstacles of

the first nine rounds have been navigated, the last two days of competition are

relatively plain sailing.

A full discussion of whether debating has moved too far away from its origins as

an audience-centred activity is beyond the scope of this paper.4 However, we will

say that we see parliamentary debate as primarily audience centered. Audiences

in Worlds style are not merely passive spectators but an interactive and sometimes

unpredictable element, which can have an indirect effect on the course of the

debate. Debates are different when there is an audience present, and every seasoned

debater knows it. A speaker with good manner draws energy and confidence from

a supportive audience; a dull, flat speech sounds more mediocre when received

with general indifference. And it is important to stress that this is not a merely

incidental feature of elimination rounds, let alone some kind of “problem”, but

absolutely central to what parliamentary debate is about. The absence of an

audience during preliminary rounds is a concession to an unfortunate practical

necessity. Ideally, all debates would have an audience.

Because audiences are crucial to its continuing appeal and relevance, then there

is reason to prefer breaking 64 teams. Worlds should showcase the best that our

discipline has to offer and this cannot be done behind closed doors, away from

an audience. Within sensible limits, the more space in the competition format

given over to public debate, the better. Although it is currently impractical to

arrange for an audience beyond the judges in preliminary rounds, adding doubleoctofinals

would double the current number of debates that have an audience.

This would reinforce the importance of the skills required to flourish in front

of an audience, thereby incentivizing their development and improving debates

beyond Worlds, and perhaps leading adjudicators to consider manner issues more

carefully than in the more sterile atmosphere of a preliminary round.

Moreover, because debating before an audience is both different and important,

breaking 64 teams actually improve the sorting function of the elimination

rounds. Debates without an audience (prelims) are missing a centrally important

element, so it is important to include a large number of teams in debates with

audiences (elimination rounds). Therefore, breaking 64 teams is preferable.

As we have argued above, one of the functions of elimination rounds is giving

people an intangible (but very real and coveted) award. Breaking 64 teams gives

out many more awards at essentially no cost to anyone. Some will argue that this

claim ignores the cost of devaluing others’ intangible awards. Though we have

already admitted that there is a kernel of truth to this, the claim is overstated.

Assuming the same number of competitors, giving 48 identical awards (instead

of 64) will result in each award being more valuable, but in fact, the awards are

not identical. Right now, if someone says “I broke at Worlds” she almost surely

implies that she made it to octo-finals. If she had made it to, say, semi-finals,

she would have said that instead. So, if 64 teams break, then the same number

of people still get to say that they made it to octofinals, which is as impressive

as before, and may even be more impressive. In short, if we look at the vast

expansion and improvement in the quality of debating over the past decade, it is

clear that giving a place in a break round to the team ranked, say, 60th in the tab

is not going to unacceptably devalue Worlds or its intangible awards.

Proposal 2: Breaking 48 Teams

Although Worlds Council has accepted that breaking 32 teams is too few and

breaking 64 teams is the next natural step in the arithmetic progression, many

people see breaking 64 as impractical and perhaps undesirable. To address this,

the tournament could break just 48 teams. There is a simple method of doing

this fairly and in a way that is consistent with the principles employed in pairings

now. The top 16 teams on the tab after the prelim rounds would break directly

to octofinals, while teams ranked 17 to 48 would debate in a double-octofinal

round. The winners of this double-octo round are then paired against the teams

who broke directly to octofinals, and things proceed as they do now.

Breaking 48 is very practical and its ease of implementation is a major virtue. It

requires no additional judges beyond what is needed for the current break, since

there are never more than 8 rooms being run in the main finals, just as in the status

quo. (Of course, if you think that there are good independent reasons to expand

the judge break, then this model would give additional opportunities for more

judges to be used in elimination rounds.) Concerning scheduling, there is enough

time during the final two days to hold five main elimination rounds, as well as

all ESL & EFL elimination rounds. ESL & EFL elimination rounds can be run

concurrently with main elimination rounds. If necessary, these could begin during

the main quarterfinals, when more breaking judges are available.

By breaking 48 team, then whenever the total field is fewer than 400

teams, all 18s will likely break. If there are fewer teams than this,

then some of the top 17 teams will likely break. The chart given earlier (figure one)

includes a column listing how many teams on 17 would have broken if 48 teams had

broken at recent WUDCs. If you believe that future tournaments are likely to be in the

range of 350 to 400 teams and you think that breaking a few of the top 17

point teams is desirable, then breaking 48 will be very appealing. It would then

reward 12% – 15% of the field with the main break, which is neither stingy nor

exceedingly generous.

Perhaps most importantly, breaking 48 provides a good sorting mechanism, for

both the elite teams on 20+ and for teams in the 17 to 19 point range. Team

seedings near the top of the tab are generally more accurate, partly because these

teams have had much more opportunity to directly compete against each other in

the top rooms, but mostly because small errors are amplified in the middle of the

bell curve. Adding or subtracting one team point from a team on 21 will only

change their rank two or three places, but for a team on 17 it could easily move

them fifteen or twenty places on the tab. The point is that we justifiably have

much less confidence in the accuracy of the rankings as we go down toward the

middle of the tab, but we have much more confidence near the top. Breaking

48 rewards the top 16 “elite” teams (mostly teams on 20+) by having them break

directly to octofinals. This avoids exposing this set of teams, which very likely

contains the best several teams at the tournament, from being exposed to any

additional risk beyond the status quo of being knocked out by a single elimination

fluke. Recall Worlds 2009, where all four top seeds were eliminated in octofinals.

We want elimination rounds to result in higher quality teams going further, and

putting the top 16 teams directly into octofinals will help do this better than a

system (like breaking 64) that forced them to compete in double-octos. This is

not unfair because their strong record rightly earns them an extra benefit beyond

just a seeding position in the bracket. At the same time, breaking 48 recognizes

that the teams ranked 17 to 48 on the tab are likely not as reliably seeded and

provides another round to sort these teams out. It is very easy to believe that the

top 17 point team in 2010 (ranked 47th) might have deserved to be ranked 28th

(adding just one team point). Since we have to believe that better teams are more

likely to prevail in this new first break round, we are likely to get higher quality

teams into the octofinals by breaking 48 than in the status quo. So, we would

likely get better teams into the later elimination rounds too.

Proposal 3: Breaking All Teams on 18 and Above

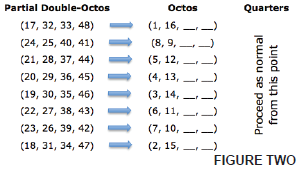

The first question often asked is how would this system work? A proposal to

advance all teams who have 18 points after nine preliminary rounds would rely

on an approach similar to breaking 48: a partial double-octo (PDO) round would

held in which teams on the low end of the break would contest a limited number

of seeds in the octofinal round. Other, higher-breaking teams would receive a bye

directly into the octofinal round.

The number of teams contesting the PDO round would vary depending upon the

number of teams with an average of at least two points per preliminary round (2+

teams). The goal of the PDO round would be to produce an octofinal field of 32

teams. To accomplish this, teams in the PDO round would contest a number of

octofinal seeds equal to the number of 2+ teams beyond 32.

At the 2009 Cork WUDC, for instance, there were 36 teams with a record of

18 or better after nine preliminary rounds. To sort the field of 36 down to 32

octofinal teams, a partial double octofinal round would be held to determine the

bottom four seeds in the octofinal round (36-32=4). The lowest eight breaking

teams would be paired into two debates; the top two teams in each debate would

advance to the octofinal round.

This approach is scalable for a larger break pool. Both the 2008 Assumption and

the 2010 Koç WUDC had 46 teams on 2+. In both cases, 14 octofinal seeds

(46-32=14) would be contested in seven PDO debates involving the bottom 28

teams from the break. The upper 18 seeds would receive a bye directly into the

octofinal round. There are two methods of handling situations where there are

an odd number of teams on 2+. Both will be discussed at the end of this section.

The proposal to break all 2+ teams shares many of the motivations and advantages

of the other proposals discussed herein. It seeks to honor the sentiment of

the 2011 Worlds Council when it voted to expand the break; it seeks a more

representative—and potentially a more diverse—break; and it seeks to increase

the proportion of breaking teams relative to those who have participated in the

championships. This proposal, however, has a number of unique advantages not

shared by breaking 48 or 64.

Chief among the advantages of this proposal is its use of a rational delineating line

between those teams who break and those that don’t. While an argument may

be made that this is an inappropriate (some have said “unfair”) point at which

to distinguish breaking teams from those who won’t break, at least the point is

grounded in the performance of the teams. Currently, and as would be the case

in each of the other proposals mentioned in this paper, the point of distinction

between breaking and non-breaking teams is determined by the convenience of

the organizers of the tournament: we currently break 32 teams—or would break

48 or 64—because those numbers are evenly divisible by four, thereby making

the task of scheduling elimination rounds easier.

This is an unreasonable basis on which to determine which teams may compete

for the championship and which may not. Deferring to the convenience of the

organizers rather than team performance forces the WUDC to rely on speaker

points to break ties between teams. Never has there been a “clean break” between

teams 32 and 33, necessitating the use of speaker points to break ties. This results

in circumstance where just a few speaker points (or even none!), out of thousands

awarded to a team during nine preliminary rounds, determine who breaks and

who doesn’t. And, this is typical.

While there may be disagreement about the value of speaker points in measuring a

team’s quality, several issues are difficult to ignore. First, it is absurd to claim that

there is a meaningful difference between a team because one averages one third

more speaker point per preliminary round—distributed between both speakers—

than the other. Speaker points are notoriously subjective and idiosyncratic; when

dealing with a quantum as small as one third or one half speaker point, the

distinctions they make are so unreliable that they are practically meaningless.

Beyond that, of course, there are circumstances in which there was no difference

in the number of team or speaker points between the 32nd and 33rd teams, which

is even worse.

Second, because speaker points attempt to evaluate teams in absolute terms rather

than relative terms, they are less reliable as a measure of quality. Though both

speaker points and team points are the product of a subjective assessment of teams’

performance, at least in the case of team points that subjectivity is constrained

to the limited context of a particular debate round. As team points are the

product of teams’ rankings within a round, adjudicators rely only on what they

have directly observed to distribute them. Speaker points, in contrast, presume

a fictitious absolute standard against which to judge teams. Adjudicators are

expected to assign speaker points to a particular speaker based on that speaker’s

performance as compared to all other speakers who have ever spoken.5 Relative

rankings are more reliable. Because their sphere of consideration is limited to

only the performance of the debaters before them, judges are more likely to

measure accurately the performance of a particular team.6 Moreover, the available

evaluative gradients are limited when ranking teams, making the determination

of those gradients easier: articulating the difference between first and second is

far easier than distinguishing between a speaker worthy of 75 speaker points and

another who receives 76.

Imperfect though they may be, speaker points do play an important role in seeding

teams for the elimination rounds. That said, there’s a significant difference between

using them for that purpose, which is inclusive, and using them to exclude teams

from the opportunity to compete in the elimination rounds.

Advancing all 2+ teams is in line with the rewards structure present in other aspects

of the tournament. Accumulating two or more points in each preliminary round

of the tournament is a significant accomplishment. In modern incarnations of

Worlds (i.e., those in which more than 300 teams participated, which is every

Worlds since 2004), the teams breaking to the elimination rounds have needed a

minimum of 18 team points to be in contention for the break. Debaters attach

significance to being ranked in the “top half ” of a round, indicating that this

accomplishment is qualitatively more valuable than being in the bottom half

of a round. During elimination rounds of a British parliamentary debating

tournament, the participants accept that the top two teams from each elimination

round will progress to the subsequent elimination round, creating a circumstance

in which both the first and second place teams “win” the round. In many ways,

accumulating an average of at least two points per preliminary round has meaning.

Another advantage of this proposal is that the size of the break remains consistent

relative to the number of participants in the tournament. In all modern

incarnations of Worlds, had all teams with 18+ points broken, the percentage of

breaking teams would have been, on average, 11.7%. That contrasts with a range

of breaking teams that is, at its lowest, 8.1% at the 2007 Assumption WUDC to

a high of 10.3% at the 2005 MMU WUDC.7

There are two plausible methods of breaking 18+ when there are an odd number

of teams on 18+. In the first method, which we call “the clean break”, all and only

18+ teams break to partial double-octos. In this case, to select exactly 32 teams to

advance to octos, one double-octo room will need to advance 3 teams, with only

one team being eliminated. For example, say there are 35 teams on 18+, the clean

break method breaks 35 teams and holds two double-octo debates: {28,31,32,35}

and {29,30,33,34}. But, the first of these rooms would advance 3 teams to octos,

while the other would advance the normal 2 teams. The rationale here is that

the debate from which three teams advance is the toughest debate, with the

lowest cumulative rankings of teams who are not the lowest seed in that round

participating. In other words, the cumulative rankings of the teams other than

the 35th seed in the first debate is 89; the cumulative rankings of the teams other

than the 34th seed in the second is 90, so the first room should be tougher. This

is significant because it provides a natural protection for the best seed in the PDO

pool; breaking three teams from that round increases the 28th seed’s chances of

making it to octofinals. Sure, it increases the chances of the 35th seed making

octos, too, but if they beat a higher seed, so be it. In the second method, which

we call “the wildcard”, the top team on 17 is added to the double-octo round so

that one additional higher seed gets a bye to octos and all the double-octo rooms

advance 2 teams to octos. For example, suppose again that there are 35 teams

on 18+, the wildcard method breaks 36 teams (including the top team on 17)

and holds two PDO debates: {29,32,33,36} & {30,31,34,35}. Each of these

advances 2 teams. The 28th seed gets a bye using this method.

Rebuttals & Responses

When considering the three proposals, we see the major question as whether to

have a fixed number of teams breaking (48 or 64) or a variable number of teams

breaking. We first discuss the objections concerning fixed breaks, then variable

breaks.

Problems with Fixed Breaks

Some concerns about breaking 64 have already been addressed, such as the

practical problems of scheduling and the concern about diluting the value of the

intangible award of breaking. There are two further concerns that apply equally

to breaking 48 or 64, along with one major issue dividing these two proposals.

Both fixed number breaking methods (48 and 64) continue to rely heavily on

speaker points, a largely capricious measure of the quality of a team’s skills.

Additionally, both of these methods make it reasonably likely that there will

be ties for the final spot in the break, and these ties will need to be broken in

some unsatisfying manner. Breaking 18+ largely avoids these problems, which

may count as a significant advantage. However, one could respond to that

although speaker points are inevitably somewhat imprecise, they are nevertheless

meaningful. Imagine a public opinion survey with a margin of error of +/- 3%,

in which people preferred A to B by a margin of 2%. Although the results are

obviously not “statistically significant” and so are not reliable, if one had to choose

based on this evidence alone, it’s still true that it’s a better bet that people prefer

A. Basically, speaker points are weak evidence when they are close, but until

we come up with something better, they are nevertheless a justifiable basis for

discrimination.

Some have objected that breaking 64 would be impractical because there are not

enough qualified judges. Defenders of breaking 64 may respond in several ways.

First, double-octofinals would only require 80 judges, using standard 5 judge

panels. There is no doubt that there are sufficiently many highly qualified judges

to fill these positions. Koc Worlds voluntarily broke 100 judges. Moreover,

breaking 64 teams may encourage organisers to expand the adjudicator break, with

important positive effects. The best way for up and coming judges to hone their

skills is to watch high-quality debates in the company of other, more experienced

adjudicators. In preliminary rounds there is precious little time to discuss debates

and for chair judges to explain why they may have seen a round in a different

way. Judging on a break round panel allows more time for reflection, discussion

and feedback. The primary purpose of WUDC is competitive rather than

pedagogical, of course, but where the two can co-exist (as with the introduction

of oral adjudication in 1999) it is to everyone’s benefit. Creating more highly

qualified judges is a good thing.

One of the main features of breaking 48 is that the top 16 teams receive a bye to

octo-finals while the other 32 teams contest a double-octo round. This reward

for breaking high up on the tab has its attractions, but some would argue that

it violates the principle that all teams at a World Championships should receive

equal treatment and have an equal chance. If we are looking for the best team in

the world, it seems only reasonable that they should have to prove themselves on

a level playing field with others; and debaters do not need any extra incentive to

finish higher up on the tab at a competition of such importance. According to

this objection, breaking 48 is preferable to the status quo, but remains a somewhat

unsatisfactory halfway house, accepting the logic of break expansion but failing

to carry it through to its conclusion. Of course, this invites the question: Would

a sufficient increase in tournament size make the next rational adjustment of the

break directly to 128 teams?

Advocates of breaking 48 can respond that their plan provides a fair playing field

with equal treatment for all. Top seeded teams earn a bye to octofinals by strong

performance in prelims, just like sports teams earn automatic spots in the playoffs

by doing well during the season. Rewarding high-performing teams with a bye is

not different in kind from rewarding them with a good seeding position, which

we already do. In fact, some argue that breaking 64 unreasonably puts the highest

ranking teams in danger of being knocked out by a fluke, thereby disrupting the

major function of the break as a sorting mechanism to get the best teams into

the late rounds. Advocates of breaking 64 can respond by arguing that it is very

unlikely for one of the top teams to be knocked out in a double-octo round. For

example, the team seeded 8th would just need to place first or second in a room

with teams seeded 25th, 40th and 57th.

Another potential objection to breaking 48 is that it might become too small

if the field of competitors continues to expand. In a field of about 420 teams,

we expect that not all teams on 18 would break if only 48 teams broke. If the

tournament grew to 500 teams, then breaking 48 would leave us breaking about

the same percentage (9.6%) as we have been breaking over the past 3 years (average

9.5%). In this case, we wonder if Worlds Council would need to revisit this issue

and again expand the break. Of course, Worlds Council could adopt a policy

of automatically increasing the size of the fixed break depending on how many

teams competed in a given year, just as happens in determining the size of the ESL

and EFL breaks. Indeed, one could argue that any break expansion policy using

a fixed size break should include a rule whereby it automatically fluctuates in size

along with the tournament size, perhaps in increments of 8 or 16. This would

presumably be done in a manner so as to try to maintain a certain percentage of

the total field as breaking.

Problems with Variable Breaks

Moving on to concerns about the breaking 18+, there are some practical concerns

and some principled concerns. Practicality objections will obviously depend on

whether we adopt the clean break or the wildcard method. Some would argue

that clean break method is unacceptable unfair because of the large advantage that

it gives all the teams who are in the double-octo room that advances three teams.

The rationale for who gets this significant advantage seems thin and insufficient.

Moreover, if teams know that they just need to avoid coming in last in that room,

it will likely change the dynamics of the debate. Considering that advocates of

breaking 18+ have put so much emphasis on the significance of placing in the

top two in a room, advancing three teams is inconsistent and troubling. The

practicality objections for the wildcard method are less significant. While it is

theoretically possible that there would be a tie for the top 17 position, this is

extremely unlikely, since speaker points in each team point bracket tend to have a

normal (i.e., bell curve) distribution, which makes for bigger gaps at the top and

bottom. Some would argue that allowing one team on 17 into the break opens

up the door to other 17s to complain that they were excluded, but the answer to

this seems just to be “we only needed one team to fill out the bracket”. Moreover,

as we just said, there will very likely be a significant drop in speaker points at this

point on the tab, which helps justify making the break there.

Another potential objection to breaking 18+ is that the size of the break would

remain too small. Given tournaments the size of those in 2009 and 2011, only

36 teams would break, which some would argue is too meagre an expansion. On

average, this method will break 11.7% of the field, regardless of the size of the

field. But some may argue that breaking 15% or even 20% is preferable. There

seems little more to say about this issue, given what we have said already. People

have very different intuitions about it. But, if you are committed to breaking a

higher percentage of the field, then you probably will want to advocate for a fixed

break system where the size of the break adjusts to the size of the field. Of course,

it is also possible to advocate for an analogous system that breaks all 17+ teams

(about 18.5%), but we expect that fairly few would advocate for such a system.

The main virtue of breaking 18+ is that it appears to offer a method of drawing a

principled line in the tab, not relying on something as imprecise as speaker points

(or worse, Article 4.a.iii) to decide who breaks. In making any decision regarding

how many to include and exclude from some award, it is ideal to find the point

where there is the most precipitous drop in the qualifications curve. The sharper

the downturn, the more clearly justified one is in drawing the line at that point.

A variable break gives us the chance to break at such an ideal place on the tab.

But, what appeared to be the main advantage of breaking 18+ may actually be its

greatest problem. That is because the top ranked team with 17 points is almost

certainly a higher quality team than the bottom ranked 18 point team, and often

by a significant degree. Call this “the discontinuity objection”. Consider this data

from the tournaments since points were standardized (fig 5). On average, the top

17 point team has 83 more speaker points than the bottom 18 point team. That

is more than 4 speaker points per partner in every round. So, it is implausible to

say that the one extra team point is better evidence of team quality than this small

mountain of speaker points. Although breaking 18+ seems to choose a principled

place in the qualifications curve, the curve actually goes up at the point where it

needs to go down to justify it as a place to draw the line. Consider the following

two charts created using the team tab from 2010, which is a typical year.

In this chart, a “quality index” has been created to give credit to teams who have

more team points. Each speaker point counts for one quality point and for

each team point the team is awarded 21.50 additional quality points.8 The

index is obviously not precise, but it is a more reliable indicator of team strength

than the rank ordering on the tab. If the best place to draw the line is a steep dip

in the quality curve, then the worst place to draw the line is right before one of

the steepest upticks in quality (e.g., the top of the 17s). Just for example, in 2007

the top ranked team on 17 was Yale A, who had the fifth highest speaker points

at the tournament—above even the top ranked team—and had been favored by

many to win the championship, having performed well the Oxford IV and

Cambridge IV that fall. Although this incident was more memorable, a look at

Worlds tabs over the past 10 years strongly suggests that the top few teams on 17

are typically of very high quality and would have an excellent chance advancing

past octofinals. This means that systems like breaking 48 or 64 would provide a

better sorting mechanism because they don’t consistently set the cut off point

such that teams just missing the cut are consistently more skilled than teams just

making the cut.

Taking all this into consideration, picking a somewhat arbitrary place elsewhere

on the curve based on speaker points seems preferable to breaking 18+. All

methods other than breaking 18+ are open to a criticism of unfairness because

the team that just misses the break can rightly claim that the speaker points used

to make the distinction that excludes them are impossible to standardize with any

precision, so that the evidence used to say that their performance was of lower

quality than the next team up the tab is extremely weak. But consider the case for

unfairness that could be mounted by the team just missing the break under the

plan of breaking 18+. They can rightly argue not just that the evidence of their

lower quality debating is weak, but that any reasonable assessment of the evidence

actually shows that they are more qualified. The latter claim of unfairness seems

much more compelling.

The suggestion being made here is not that the order in which teams break (i.e.,

their ranking on the tab) should be changed to match something like a quality

index. Such an approach seems fraught with problems, so we seem stuck with a

ranking that gives strict (lexicographic) priority to teams with more team points.9

Rather, the point here is that since we need to work down this list in order, it

is best to avoid making the cut-off precisely where there is a significant quality

discontinuity in the wrong direction.

Since the fairest place to make the cutoff for the break is where the drop off in

team quality is steepest, one could modify the breaking 18+ system to also include

the top 2 or 3 teams on 17 points. Call this the “Top 17+ plan”. Breaking 18+

using the wildcard method already needs to allow in the top team on 17 when

the number of 18+ teams is odd, and this Top 17+ plan simply acknowledges

that the top teams on 17 are often exceptionally talented and worthy of breaking.

More to the point, figure seven shows how there tends to be a precipitous decline

in team quality at exactly this point. And, as a bonus, ties in points are unlikely

at this point on the curve. Essentially, the point here is that breaking at 32, 48,

64 or any particular number of teams cannot give us good reason to expect the

break to coincide with a steep downturn in quality. Breaking after the bottom

18 team all but guarantees that the break coincides with a steep upturn in quality.

But by including 2 or 3 of the top 17s, we have excellent reason to expect that the

break will coincide with a fairly steep decline in team quality, and therefore have

maximum justifiability.

Response to the Discontinuity Objection

A legitimate concern expressed regarding this proposal is that the lowest ranked

18 point team may have significantly fewer speaker points than the top ranked 17

point team, indicating that the bottom 18 point team is of a lower quality than

the top 17 point team. Although the manner in which we determine and reward

the merit of a team’s performance is not without flaw, the argument that the

lowest 18 point team is less deserving than the highest 17 point team is troubling.

First, we as a community have agreed that team points are more meaningful

than speaker points. We use team points to power-pair teams throughout the

tournament to test teams against others of similar records. In fact, the powerpair

approach of the WUDC deliberately ignores delineations within a particular

record bracket, preferring a random match of teams with similar records to one

in which the teams with the highest speaker points within a bracket are paired

against teams with the lowest speaker points. Moreover, breaking teams are

determined first and foremost on their team points records; we rely on speaker

points only to seed teams within elimination rounds (and, in the status quo, to

determine which teams make the break).

Finally, to criticize this proposal because “lower quality” teams would advance

(i.e., that 18 point teams with low speaker points would advance while nonbreaking

17 point teams high speaker points would not) ignores that this is the

status quo. In three of the last four WUDCs, several non-breaking teams on 18

had more speaker points than the lowest-ranked 19-point team.

Summary

There are legitimate arguments in favor of all the proposals that we have discussed,

but in conclusion we would like to quickly survey their major advantages and

disadvantages of each according to the standards identified earlier in this essay:

1) the practicality of their implementation; 2) how effectively they emphasize the

importance of the audience; 3) how appropriately they distribute highly valued

intangible awards; 4) the fairness of their implementation; and, 5) how effective

they are at sorting teams, such that the higher quality team are likely to progress

further in the tournament.

Regarding practicality, all of the proposals discussed here are entirely feasible.

Any differences in ease of use are too minor to base a decision on. One long-term

practical consideration deserves a brief discussion. As mentioned earlier, endorsing

any new particular fixed size break risks just kicking this same problem down the

road to when the tournament expands further (or perhaps contracts). For this

reason, we argue that any expansion plan using a fixed size break should build in a

rule that automatically adjusts the size of the break to the size of the tournament.

Although we make no specific proposal, figure nine would be just one example.

This one example is of a system designed to ensure that at least 12.5% of the field

breaks (which almost certainly includes all teams on 18+). Such a system could

be made finer grained by adjusting the break size by increments of 4 teams, which

would keep the maximum break at 14% of the field.

And, of course, these numbers could be adjusted in myriad other ways to

accommodate people’s beliefs about what the size of the break should be. That

the important thing is that once such a graduated fixed break system is set, Worlds

Council would be unlikely to need to take up this issue again any time in the

foreseeable future. The variable size break plans we’ve discussed (e.g., breaking 18+)

will automatically adjust to the size of the tournament.

Regarding exposing teams to audiences, all we can say for certain is that plans

that break a greater percentage of the field are obviously better at increasing the

exposure of teams to an audience, and thereby gaining the advantages mentioned

earlier that come along with this. So, this consideration seems to favor a graduated

fixed break system with higher percentages of teams making the break. The

relative importance of this consideration is a matter of considerably more dispute,

and we cannot settle that here.

Regarding award distribution, there are advantages and disadvantages to all the

systems. A smaller break makes the intangible award of breaking more valuable,

so this is a reason to prefer expansion systems that break a smaller percentage of

the field. In contrast, it is also desirable to recognize more people’s achievement,

even if just with an intangible award, which is reason to prefer systems that break

a larger percentage. Of course, none of this will change that only 32 teams will be

able to say that they “made it to octofinals”. Intuitions vary considerably on what

percentage of the field at the top of the tab deserves the special recognition of

such an intangible award, and we don’t see that further discussion here will likely

change this for most people. However, although it is only a rough guideline, we

agree that plausible proportion of teams deserving such recognition falls in the

range of 10% to 20%.

Regarding fairness, none of the proposals is without problems. Critics of fixed

break plans argue that these all rely on insignificant differences in unreliable

speaker points to make the very important distinction between who breaks and

who doesn’t. The unfairness here stems from the system’s unreliability, and it is

even worse in cases where a tie occurs, which is not that unusual. The criticism of

variable break plans depends on which method is used. Critics of the clean break

method of breaking 18+ will claim both that it gives a major unfair advantage to

some teams when an odd number of teams break and that it unfairly makes the

cutoff for breaking immediately before a significant increase in team quality. The

former claim is of a procedural injustice, while the latter claim is that the proposed

system mistakes clarity for justification. Critics of the wildcard method will argue

that it is unfair to violate the defining principle of the system of breaking 18+

(by including the top team on 17 in the break) just because an odd number of

teams happened to be on 18+. The claim here is that this is unfair because it is

inconsistent or capricious. Finally, critics of breaking the top 2 or 3 teams on

17 argue that this is unfair because this method still relies on unreliable speaker

points, even though the gaps between teams tend to be larger at this point on

the tab. Additionally, advocates of the clean break at 18 argue that averaging at

least 2 points per round (i.e., achieving a ‘winning average’) is itself normatively

significant, such that these teams deserve to break in a sense that a team on 17

with high speaker points does not deserve to break. In other words, deserving

to break is in an important sense not a comparative judgment about how a team

placed on the tab compared to how well other teams did.

Regarding sorting teams, we want to make three observations. First, there is a

sorting advantage to getting more teams in front of an audience because this is

essentially a public event and the most effective way to sort competitors’ public

debating skills is by seeing them debate in public. Second, having a partial

double-octo round is an effective way to protect and reward top teams who have

performed exceptionally in preliminary rounds. More of the most talented teams

are likely to make it to late elimination rounds if some of the top seeded teams

break directly to octofinals. Third, a system that allows some 17 point teams

to break will of course allow the top 17 point teams to break, and these are

often very high quality teams that may justifiably make it into quarters or even

later elimination rounds, improving the sorting. Unfortunately, there is also the

disadvantage that these high-quality top 17 teams may disrupt the sorting in

other ways because their seeding is not commensurate with their skill.10 The

sorting advantage of breaking mid-range 17 point teams is less obvious, but it is

possible that some of these teams will flourish in front of an audience.

In the end, as in the beginning, the authors of this paper do not agree on the best

approach to expanding the break. However we hope that we have identified the

most important considerations that go into making this decision so that future

discussions will be better informed and the best decision made more likely.

10 Of course, this is only a problem if one admits that the skills of the top few teams on 17 are

significantly greater than their rank on the tab suggests.

References

1 http://worlddebating.blogspot.com/p/history-of-wudc.html [Accessed July 6, 2011]

2 For more on the development of Worlds, see Hume, A. (2009). “Citius, altius, fortius: the

evolution of Worlds debating”. Monash Debating Review.

3 To see why, first consider why a single-elimination bracket in any two contestant event (e.g.,

tennis) will only be theoretically effective at sorting the single best player if we presume that the

initial seedings are not already accurate. It is very possible that the two best players will meet

before the finals, so being in finals doesn’t reliably indicate that you are one of the two best players,

being in semi-finals doesn’t reliably indicate that you are one of the four best players, etc. The

same problem exists with BP debate, except that each single elimination contest advances two

teams. Of course, all this is true even if we grant that judge panels in elimination rounds never

make errors. The problem is mathematical, not practical.

4 If one looks at the history of competitive debating, it is hard to resist the conclusion that

when a debating format moves away from being an audience centred performance, that style

quickly degenerates into fast and often incomprehensible oral battles filled with jargon and of

little interest to public intellectuals or anyone outside itself.

5 And, frequently, against those teams who haven’t yet spoken. I routinely hear adjudication

teams instruct judges at the outset of a tournament that the average for all speakers points should

be 75 speaker points, thereby requiring judges to compare speeches they’re hearing in round one

against speeches they have not yet, but may eventually hear in round 9. This also assumes that

an individual adjudicator at a WUDC will see enough speakers at that tournament to understand

what the “average” is, a logistic impossibility given that most adjudicators will typically see only

about 10% of the speakers at the tournament—assuming that they don’t see one team twice—and

given that no mechanism exists for ensuring that particular adjudicators see a representative crosssection

of the quality of debaters participating at the tournament.

6 For a more thorough treatment of the advantages of relative rankings over absolute ratings, see

Goffin, Richard, and James Olson. “Is It All Relative? Comparative Judgments and the Possible

Improvement of Self-Ratings and Ratings of Others.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 6.1

(2011): 48-60. Sage Publications. Web. 13 July 2011.

7 If one looks further back in WUDC history, an even higher percentage of teams have broken.

Consider the 1999 Manila WUDC, in which 173 teams participated and 18.3% of teams broke.

As we note elsewhere in this paper, a proportionally larger number of breaking teams was typical

at the time the octofinal round was set as the first elimination round for the WUDC.

8 Quality Index = Total Team Speaker Points + (Team Points x 21.50) The 21.50 in this formula

represents the average difference in total prelim speaker points between teams that are separated

by one team point, calculated from the data over the past five years. So, the formula gives exactly

this much credit toward the quality index for each team point. Those skeptical of this formula

should note that even adding twice as many quality points for each team points would clearly

show the same phenomenon. Teams at the top of their team point bracket will almost invariably

be stronger than teams at the bottom of the next higher team point bracket.

9 At this point, one might think that it is a good idea to discard the traditional lexicographic

method of ranking teams on the tab (where speaker points are only considered to break ties in

team points) and replace it with a quality index. The problem is how to convert two numbers

measuring team skill into a single number. As done in the charts, multiplying the more important

number (team points) by some factor can produce a quality index, but unless everyone can agree

on what that factor should be, the resulting index would likely lack the legitimacy that is necessary

for the very important role of determining the break. The factor used in the above charts is not

arbitrary, but then again, no specific awards or privileges are associated with its precise results.

(The conceptual point made by the chart would have been supported by any multiplying factor

vaguely in the same range.) In short, teams who just missed the break based on a quality index

would almost surely perceive the chosen factor as capricious and entirely unfair. Such discontent

would not be worth the trouble.